|

The goal of the Bermuda

Turtle Project is, "to promote the conservation of marine turtles

through research and education". The project team has made notable

progress to date and has exciting plans for expanding research and

education objectives. The goal of the Bermuda

Turtle Project is, "to promote the conservation of marine turtles

through research and education". The project team has made notable

progress to date and has exciting plans for expanding research and

education objectives.

The Bermuda Turtle Project has assembled important data sets on size

and maturity status, growth rates, sex ratios, residency, site

fidelity, genetic diversity, and movement patterns in immature green

turtles in Bermuda waters. We have assembled similar, but much

smaller, data sets for Bermuda hawksbills.

Our findings show that Bermuda serves as a year-round habitat for

immature green turtles and hawksbills, providing a 'developmental'

feeding ground for nesting beach populations that are located mostly in the Caribbean,

but may exist as far away as Cyprus in the Mediterranean.

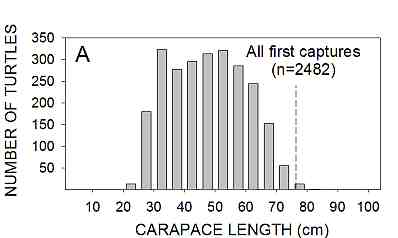

Our data show that green turtles arrive at Bermuda at a size of

about 25 centimeters (10 inches) and leave by the time they have grown

to approximately 75 centimeters (30 inches). Stranding records show a similar distribution of sizes, with a very

small number of turtles that are smaller than the minimu size of

turtles caught in the net. Our data show that green turtles arrive at Bermuda at a size of

about 25 centimeters (10 inches) and leave by the time they have grown

to approximately 75 centimeters (30 inches). Stranding records show a similar distribution of sizes, with a very

small number of turtles that are smaller than the minimu size of

turtles caught in the net.

Green turtles are about the size of a silver dollar when they hatch,

and take about thirty to fifty years to reach maturity.

Thus, it is easy to see how a project such as this one, which has been

gathering data since 1968, is so valuable. It takes years to collect

enough data to understand life history patterns.

The gaps at either end of the size distribution graph for green

turtles in Bermuda represent the epipelagic phase that

follows hatching, previously known as the 'lost year,' and

the large but still immature sub-adults that have departed to the

adult resident habitat.

During the years 1990

through 1992, most turtles captured by the project were laparoscoped.

In this procedure, a small incision is made through the body wall of

the turtle and the gonads are viewed using a surgical scope to

determine sex and maturity status. By examining 138 immature turtles, we were able to establish that none were mature

and to calibrate a hormone assay that allows us to determine a green

turtle's gender from a blood sample. During the years 1990

through 1992, most turtles captured by the project were laparoscoped.

In this procedure, a small incision is made through the body wall of

the turtle and the gonads are viewed using a surgical scope to

determine sex and maturity status. By examining 138 immature turtles, we were able to establish that none were mature

and to calibrate a hormone assay that allows us to determine a green

turtle's gender from a blood sample.

Caldwell and Mowbray wrote in 1954 that green turtles in Bermuda were

probably itinerant and were delivered to the island annually by the

Gulf Stream. By sampling year round, we were able to show

that green turtles are year round residents. We actually found a density in January matching, if not surpassing, that of the

summer months. This is possible because Bermuda waters do not drop drastically in

temperature during winter months. Bermuda

waters stay as warm as those of the SE coast of Florida.

Information from local recaptures has shown that young green turtles

in Bermuda establish specific feeding areas. Even if displaced, they

usually return to these particular sites and may stay there for many

years.

The greatest number of times that a single individual turtle has

been captured in Bermufa is seven. This turtle was captured on the same grass flat

each time. The longest period of time over

which we know that an individual has remained in Bermuda waters is 14

years. Based on the size at first capture, these 14-year residents were probably in Bermuda for a few

years before their first capture and probably stayed a few more

years before departing. So, we expect a maximum residency time of about

twenty years for green turtles.

Using a Geographic Information System (GIS) we can visualize

patterns of habitat use that may be related to seasonality, turtle

size, sex, and other biological and physical characteristics of

the habitat. Analysis of turtle distribution data with GIS will be of

great benefit to management authorities in identifying critical habitat.

Blood samples are taken

from each turtle to determine gender and genetic identity. Serum samples are sent to Dr. David Owens at the Grice

Marine Laboratory, College of Charleston, SC, where the amount of

testosterone in the blood is determined. These data are used to

determine the sex of immature animals. A second blood sample is preserved in a

buffer which stablizes the DNA so that it can be used to determine genetic identity. Blood samples are taken

from each turtle to determine gender and genetic identity. Serum samples are sent to Dr. David Owens at the Grice

Marine Laboratory, College of Charleston, SC, where the amount of

testosterone in the blood is determined. These data are used to

determine the sex of immature animals. A second blood sample is preserved in a

buffer which stablizes the DNA so that it can be used to determine genetic identity.

We have been compilng and analyzing genetic sequence

data from Bermuda turtles since 1996. Our studies show that Bermuda green turtles

match gene sequences of green turtle populations from Florida,

Mexico, Costa Rica, Cuba, Aves Island (near Dominica), Suriname, Cyprus,

and either Ascension, Brazil or Guinea Bisseau in the South Atlantic.

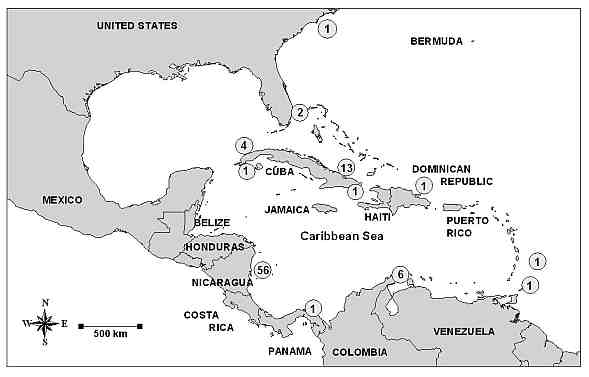

As of 2005, 88 green turtles caught and tagged in Bermuda have been

found overseas in Venezuela, Colombia, Nicaragua, Panama, Cuba, the

Dominican Republic, Saint Lucia, the U.S. and Grenada. This information, along with genetic results, highlights the regional

significance of Bermuda to the green turtle. It also confirms the need

for international cooperation in sea turtle conservation. Unless

green turtles are protected on the nesting beaches and in their adult

ranges,

Bermuda may lose its feeding aggregation, in spite of efforts to

protect turtles

in Bermuda waters. To date, the project has recorded only one

international

recapture of a hawksbill turtle. The animal was captured with a spear

gun off the east coast of Grenada eleven years after being tagged in

Bermuda. As of 2005, 88 green turtles caught and tagged in Bermuda have been

found overseas in Venezuela, Colombia, Nicaragua, Panama, Cuba, the

Dominican Republic, Saint Lucia, the U.S. and Grenada. This information, along with genetic results, highlights the regional

significance of Bermuda to the green turtle. It also confirms the need

for international cooperation in sea turtle conservation. Unless

green turtles are protected on the nesting beaches and in their adult

ranges,

Bermuda may lose its feeding aggregation, in spite of efforts to

protect turtles

in Bermuda waters. To date, the project has recorded only one

international

recapture of a hawksbill turtle. The animal was captured with a spear

gun off the east coast of Grenada eleven years after being tagged in

Bermuda.

Between 1996 and 2008, we deployed eight satellite transmitters

attached to Bermuda green turtles. These transmitters transmit

messages to satellites when the turtles surface to breathe. Data

(latitude, longitude, location accuracy, dive frequency and duration,

and temperature) are uploaded to the satellite. Positions of the turtle

are plotted using the Geographic Information System developed for the

project. One of these transmitters sent data for fifteen months. Most

positions recorded were centered on the capture area, and it is

believed that the turtle did not travel any significant distance.

However, one of the seven turtles fitted with a transmitter did

make a significant journey.

In August 1998, a 78.6 - cm green turtle carrying a satellite

transmitter departed the Bermuda Platform about two weeks after

attachment. We were able to record her remarkable journey of

approximately 1,500 kilometers (932 miles) which took her south to

the Dominican Republic and then west to Cuba. This turtle, named

"Bermudiana," was originally captured on August 5th with a net on the

seagrass flats off the northwestern end of Bermuda. Location and dive

data were received for the turtle on a daily basis. The turtle was just

north of the coast of the Dominican Republic as Hurricane Georges

passed by, but there were no observable effects. Several days later,

however, transmissions changed dramatically and eventually stopped. We

believe that Bermudiana was captured off the eastern tip of Cuba, near

the town of Baracoa (map shown).

Starting in 2011, we attached transmitters that can take GPS location data, in addition to standard Argos data. These will allow a much more precise understanding of how young green turtles use Bermuda waters. Results from these transmitters can be seen here.

The Bermuda Turtle Project serves as a useful vehicle for public

outreach and education. In addition to the many volunteers

who join the field efforts each year, teachers, school classes, and

eco-tour groups are educated about the plight of the endangered green

turtle through slide shows and lectures. Guest scientists

contribute nearly annually to the project, the associated course, and

to public outreach via lectures. The project has benefitted greatly by

visits from Robert George, Tierry Work, Brendan Godley, David Owens,

Marydele Donnelly and Robert van Dam.

The Bermuda Turtle Project hosts an International Course on the Biology and Conservation of Sea Turtles

each year. The two-week course consists of lectures, class discussions

of assigned readings, a necropsy session, and extensive field work

capturing immature green turtles.

Some of the basic findings of the project appear in a Bulletin of the American Museum of

Natural History. This publication is available online at: http://digitallibrary.amnh.org/dspace/handle/2246/6126

The Bermuda Turtle Project looks forward to sharing our new discoveries with you!

Return to Top of Page

|