|

The green turtle, the most common sea turtle in Bermuda's waters,

once nested abundantly on our beaches. William Strachy's narrative of

1610 noted "even then the Tortoyses came in again, laying their eggs

(of which we should find five hundred at a time in the opening of a

shee turtle) in the sand by the sea shoare." New World explorers

wrote of huge herds of turtles. The explorers would capture many of the

turtles, which were capable of remaining alive for weeks in the holds

of their ships, providing fresh and nutritious meals for their long

ocean voyages.

In 1610, settlers noted that "on the shores of Bermuda, Hogges, Turtles, Fish and Fowle do abound as dust of the earth."

With recorded takes in the accounts of early settlers of more than 40 turtles per boat per day, it was

not long before the local stocks of sea turtles were noticeably

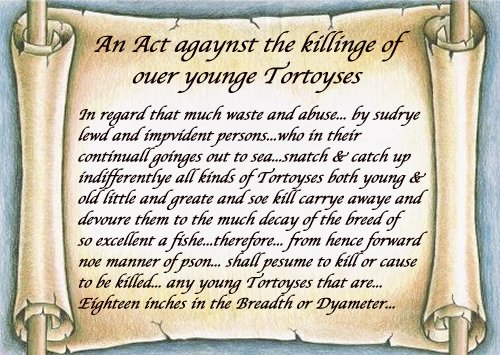

depleted. In 1620, only eleven years after Bermuda's colonization, an

act of the Bermuda Assembly against the killing sea turtles was passed.

This may well be the New World's first written conservation

legislation. In spite of this early protection of young turtles, larger turtles were

fished until 1973. If our forefathers knew then what we know now - that

the sea turtles growing up in Bermuda were all from other nesting beach

populations - then they surely would have protected the nesting

females and Bermuda's nesting population may not have become

extinct in the early 1800s.

In an attempt to reestablish a nesting population in Bermuda, over

twenty-five thousand green turtle eggs were transplanted from Costa

Rica in the 1960s and 70s by the Sea Turtle Conservancy and buried on

beaches in Bermuda. More than sixteen thousand of these eggs hatched.

Based on the premise that turtles incubated at their home beach return

to that beach to lay their eggs, it was hoped that these transplants would

eventually return to reproduce in Bermuda. However, no nesting by green

turtles in Bemuda has been documentd since the transplant experiments

occurred, and it seems unlikely that the effort will succeed.

Studies were made on the behaviour of these hatchlings by Jane Frick. She found that, upon release, the

hatchlings all took a direct course to the southwest away from the

island and out into the open ocean. This work heightened local

awareness and led to further legislation in 1973. Since that time, all

sea turtles have been completely protected locally.

The Bermuda Turtle Project was initiated in 1968 by Dr. H. Clay

Frick II, Trustee of the Sea Turtle Conservancy, in cooperation with

the Bermuda Government. Since Dr. Frick's retirement in 1991, the

project has been under the direction of the Bermuda Aquarium,

Museum and Zoo, in collaboration with the Sea Turtle Conservancy, and the

Bermuda Zoological Society.

The

shallow grass flats of Bermuda provide excellent grazing areas

for green turtles and coral reefs provide habitat for hawksbills,

although in smaller numbers. The

turtle tagging project is one of the longest-running projects of this

kind in the world. It has developed into a multi-faceted study of sea

turtles. The

shallow grass flats of Bermuda provide excellent grazing areas

for green turtles and coral reefs provide habitat for hawksbills,

although in smaller numbers. The

turtle tagging project is one of the longest-running projects of this

kind in the world. It has developed into a multi-faceted study of sea

turtles.

The primary aim of the Bermuda Turtle Project is to fill in critical

information gaps in the life history of sea turtles that inhabit Bermuda waters and to make

that information available to scientists, managemers and the public.

In order to protect sea turtles, we must know where they occur, in

what numbers, at what times, and what factors contribute to their

mortality. In essence, population and life history models need to be

refined to include all that we can learn about their entire life cycle.

The special contribution that the Bermuda Turtle Project can make is to

elucidate the biology of sea turtles in developmental habitats --

places where young turtles grow up in the absence of adults.

Return to Top of Page

|